Higher for longer: Implications of Interest driven Cash Flow Growth in Net Cash Companies

How to view interest income in valuing companies

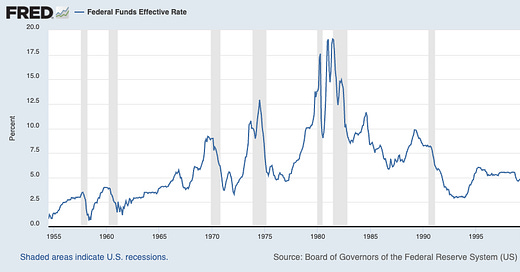

Over the last two years, interest rates have seen one of the fastest increases ever, going from zero to five percent in a year. While this pressured equity markets and brought highly leveraged companies to their knees, there have also been winners. In this article, I want to discuss the implications of high interest rates on companies with large net cash positions and float and how we should view this as long-term investors.

I like to invest in high-quality businesses. While there is no strict definition to define the quality of a business, it often goes hand in hand with a prudent capital structure and often fortress balance sheets. A fortress balance sheet means a large cash balance without much debt. This makes the company independent from outside capital and they have their destiny in their own hands. Three examples of fortress balance sheets in my portfolio and investable universe are Adyen, Veeva Systems and Pluxee. They all have large net cash positions on their balance sheets, as seen below.

Let’s now look at net income, interest income (labeled interest expense here) and EBIT. If we go through the balance sheet, EBIT represents operating income: Earnings after accounting for all production costs and depreciation and amortization. Then, we subtract taxes (usually between 15% and 25% for most businesses) and interest expenses to arrive at net income. EBIT is further up on the balance sheet, and fewer expenses are deducted, so it typically is higher than net income. Below, we can see that interest income has rapidly climbed for these companies (on Pluxee, it’s less visible because of its recent IPO/spin-off from Sodexu and related messy financials). For Veeva, net income even exceeds EBIT. The interest received has a large impact on the overall profitability of the business. Great, right?

Well, it depends. The issue with interest income is that it’s volatile. While companies can control their net cash position, they can’t control the interest rate environment! The last few years saw tremendous tailwinds from the climbing of interest rates. It’s especially severe for Adyen, which saw interest income grow from 10 million to 241 million in just a year. Interest rates have a lagging effect because, most of the time, cash is invested in bonds or other money market instruments. These often have a maturity of a few years. If the old bonds expire and the company gets the money back, they can buy new bonds at much higher interest rates. This means that even if interest rates go down again, they’ll enjoy higher interest income for some more time. So, how should we see interest income? In my opinion, investors shouldn’t try to extrapolate interest income growth. Businesses with significant interest income as part of the business model should be primarily valued based on operating income without factoring in continued interest income growth. I haven’t put too much emphasis on this myself in the past, but I’ll be looking to change that.

Float businesses models

Lastly, let’s talk about float-based business models. Float represents customer funds, so cash that is trusted to the company but isn’t theirs. The huge benefit of float business models is that you can invest it until you have to pay it out again. Adyen and Pluxee, for example, hold a large amount of customer funds on their balance sheets, representing the majority of their net cash position.

We should differentiate this from companies without any float-based revenue. Veeva does not receive customer funds; all their net cash is theirs. In this case, we should ask ourselves, is this the optimal capital allocation? Does Veeva really need $4 billion in net cash and can’t that be reinvested into the business at higher rates of return or returned to shareholders? Net cash can make sense if you are in a capital-heavy industry or preparing for a large M&A deal. In Veeva’s case, however, the company operates in a capital-light industry and hardly ever does M&A. We investors should be skeptical of such a cash pile in this situation.

Conclusion

I hope that I have spurred some thoughts in your mind regarding interest income, especially in rising-rate environments. Interest income is often a part of a business model but can also hint at a suboptimal capital allocation framework. Interest income should be viewed or at least acknowledged differently from operating income.

I’d recommend adding Airbnb to that list. Incredible float which generated over $700 million of interest income in 2023 and an asset light business model.