I recently was asked by a subscriber to explain my valuation methodology in more detail, so let’s talk about valuation and how I do it! First off, valuation is an art, not a science. There are no right or wrong ways to do it (okay, maybe there are wrong practices to avoid) as long as it works for you.

My method is the inverse discounted cash flow model. I already explained the concept a bit in this post, but let’s go deeper. Let’s use Alimentation Couche-Tard $ATD as an example. ATD is one of the largest convenience store chains in the world and a fantastic business with great capital allocators and skin in the game.

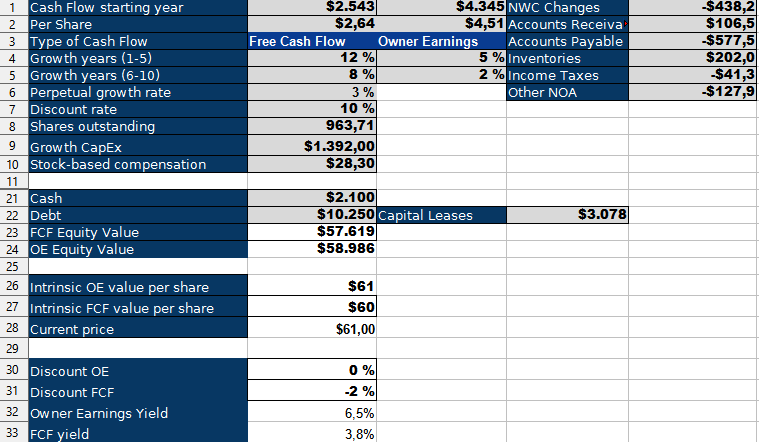

Below, you can see the full model. In the first three lines, you see the Free Cash Flows (FCF) and Owner Earnings (OE), full values and per share, for the business in the last twelve months. I recently published a post explaining why I adjust FCF to arrive at OE.

The beauty of my inverse DCF model is that you only have to make three decisions; the rest is just data from the trailing twelve-month period. The three variables are:

Perpetual growth rate

Discount rate

Growth CapEx

The way a DCF works is you discount the cash flows for a year by the discount rate. You then sum up (most of the time) the next 10 years of projected cash flows, and each year’s cash flows are discounted at a higher rate to attribute the time-weighted decay of value money has: A dollar now is worth more than a dollar ten years out. To do this you need a discount rate. This basically represents your required rate of return, I often increase the discount rate to account for risks and to make the valuation more conservative. If you want to be truly scientific you can use the WACC of a company, but I don’t like this approach and I’d rather stick with set discount rates:

10% for a high-quality, noncyclical business with recurring revenues

12% for a high-quality, slightly cyclical business

15% for a high-quality, cyclical business or one with other relevant risks

The disadvantage of a DCF is that it runs for ten years, while businesses (hopefully) exist for much longer. The perpetual discount rate represents the growth rate into eternity (at least in theory). I usually just take 3% for this, as it represents the expected long-term GDP growth rate for the US.

Below, you see the internal calculations of the model. OE is the Owner Earnings for the year, PV is the present value of the OE in the given year (discounted by discount rate^numer of years), and the sum of PV is the total sum of the 11 periods. The last period is the Terminal value; this is the value that is outside of the 10-year time frame, the value into eternity. The terminal value is calculated with an exit multiple = Discount rate-perpetual growth rates, so, in this case, it is 7%. That means we take the year 10 value, add the growth rate on top, and then divide it by 7% to get the terminal value. The terminal value often is a very large part of the value of an investment. However, the higher the growth rate of a business, the more value it has in the first ten years. In lines 4 and 5 you can see the estimated growth rates. I use two values, to model a deceleration over the years, as happens with most businesses. We’ll get these later.

If you want to understand the Growth CapEx portion better, please read the article I mentioned at the beginning. In short, Growth CapEx is CapEx, which is not necessary for the business and can be cut; thus, adding it to FCF makes sense to arrive at the actual cash generation abilities of the business.

In lines 21-24, you can see the cash and debt of the business (I include capital leases as well, but this does NOT affect the calculation. It is just to visualize how much of the debt is capital leases). The equity value lines represent the result of the value the DCF arrives at plus the net cash/debt of the business.

Now to growth rates: Unlike in normal DCF models, we do not estimate the growth rate. We adjust the growth rates for years 1-5 and 6-10 until the intrinsic value per share (lines 26/27) equals the current stock price (line 28). That way we arrive at the growth rate the business needs to achieve to satisfy the market valuation.

Lines 32 and 33 represent the cash flow yield on enterprise value as a visualization or shortcut to valuation.

In this example, we can see well how much of a difference is between the FCF and OW of Alimentation Couche Tard. The business invests a lot of money every year in expanding its store network and improving it. This cash could be returned to owners instead, so we adjusted it. Also, we had large movements in Net Working Capital, especially in the form of Accounts Payable. This means that they had a $577 million headwind to FCF from paying suppliers later. This is not a sustainable cash flow generation, but rather yearly fluctuation, so I prefer to adjust it out to get to the true cash flow generation of the business.

After we have done all this we need to look at the required growth rate of the business and decide for ourselves if we find it to be realistic. Ideally, we require a growth rate below what we expect for the business. Couche Tard, for example, has a target of around 10% EBITDA growth over the next five years (we can use EBITDA as a proxy for cash flows), significantly higher than the required OE growth rate. The stock could be undervalued.

I hope this helped you to understand my valuation methodology better. To reiterate, valuation is an art, not a science. There are other ways to value businesses and I’m not saying my way is the best or most accurate. However, I think it provides a relatively objective view of the business and removes a lot of fluctuation from cash flows. I will continue to use this model in my work. If you want to see a slightly different approach to valuation, check out this post from my friend CompoundingTortoise.

Great article! Have you considered changing the duration of the DCF? If ACT has a big moat, you could project onto 15 years before arriving at the terminal value. My second question: is the growth capex not linked to the fcf growth rate you assume?

Thank you for the writeup! Will you be able to share the template with paying subscribers?